Vegetation Health

Measuring plant health from space

Agriculture is vital for sustaining the global population, but larger plantations make crop health monitoring challenging. Fortunately, near-infrared light, observed by satellites, helps us assess crop health effectively.

Light from sunlight to produce energy through photosynthesis. Visible light has a wavelength between 0.4μm and 0.7μm.Near infrared light (just a little longer in wavelength than visible light) is not useful for photosynthesis and is reflected by the cell structure of the leaves. Consequently, the healthier a plant is, the more near infrared it reflects and the less visible light it reflects (because it is using this for energy).

Monitoring vegetation health is important in assessing ecosystems’ conditions, predict yields, manage resources and detect environmental changes. It helps researchers and agricultural institutions make informed decisions about agriculture, conservation, and land management, supporting food security and environmental sustainability.

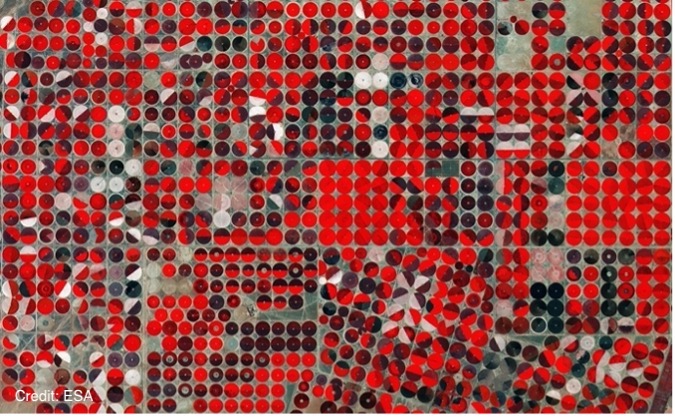

A false colour image of agriculture structures in Saudi Arabia:

In the image, vibrant red tones indicate dense, vigorously growing vegetation, while lighter shades of red, pink, and green signify a decrease in plant vigour. Sentinel-2 is designed to provide images that can be used to distinguish between different crop types as well as data on numerous plant indices, such as leaf area index, leaf chlorophyll content and leaf water content – all of which are essential to accurately monitor plant growth.

This kind of information has obvious economic benefits such as helping make informed decisions on how much water or fertiliser is needed for a maximum harvest or for forming strategies to address climate change, but is also important for developing countries where food security is an issue.

In 2025 ESA will launch an new satellite, using novel technology the Fluorescence Explorer (FLEX) will yield information about the health of the world’s plants. The information gathered will be used to improve our understanding of how carbon moves between plants and the atmosphere and how photosynthesis affects the carbon and water cycles.

The planet’s growing global population is placing mounting pressure on the production of food, animal feed, biological fuels and pharmaceutical products. It is estimated that there will have to be more than a 50% increase in agricultural production by 2050 to meet demand. Understanding plant health and productivity is therefore essential to managing resources.

Although photosynthesis is one of the most fundamental processes on the planet, it has not been possible to measure it directly on large spatial scales. However, when plants photosynthesise, they emit a faint fluorescent glow.

This glow is invisible to the naked eye, but, remarkably, it can be measured from space. Carrying a novel instrument called the Fluorescence Imaging Spectrometer, FLEX will measure this fluorescent signal to shed new light on the functioning of our vegetation. The information will be used to assess the functioning, health and stress of plants.

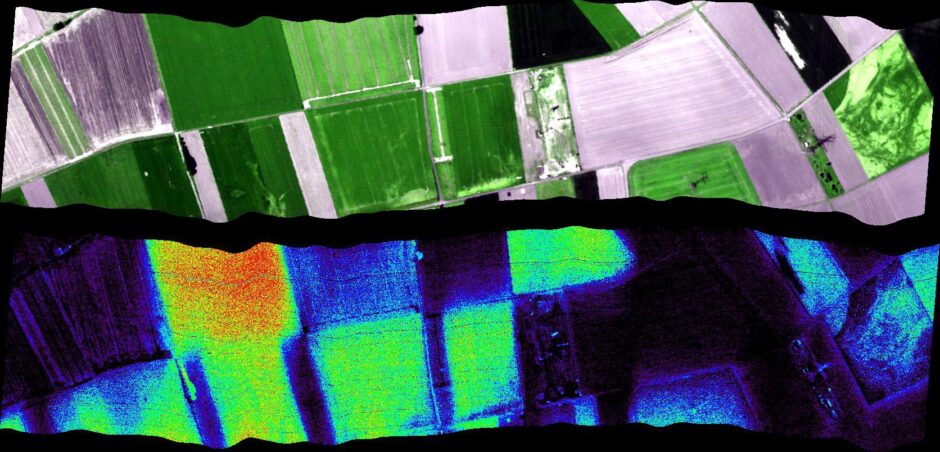

The image above shows highly fluorescent sugar beet, which is a twice-yearly crop that is still green with a dense healthy canopy in October. The image shows that it is one of the most photosynthetically active crops at this time of the year. By comparison, apple orchards, natural pine and mixed forests fluoresce less. Areas that lack vegetation such as bare soil, roads and buildings do not fluoresce at all.